With the advent of the Covid-19 pandemic, millions of office workers worldwide were forced to work from home (WFH) for the majority of 2020. With this massive shift in employee work practice, many forecasters are predicting a long-lasting negative impact on offices, despite the recent race to roll out vaccines across the globe. Office companies predictably disagree and highlight the long-term need for their assets while acknowledging that WFH is here to stay, and is not just compatible but complimentary rather than a substitute for work from offices. We examine the various arguments on both sides of a debate that is unlikely to be concluded soon and see more a mixed impact.

We expect WFH is here to stay and will result in companies and employees adopting a hybrid model whereby a few days in the office will be mixed with a few WFH days. Some impact around increased collaborative workspace, possible (not probable) de-densification, some degree of hot desking with all its associated advantages and disadvantages, and increased health protocols (vaccine passport to work in an office anyone?) are also likely.

We consider that prime offices in well sought-after locations – particularly those with strong sustainability, wellbeing and technology characteristics – should remain attractive enough for employees to go back to. Non-prime offices in less attractive locations could suffer from low tenant demand and rental declines, or even repurposing.

Location-wise, some office markets such as London’s City or West End, Paris’ Central business district, and Berlin, Barcelona and Madrid entered the pandemic with relatively low vacancy rates and are therefore better prepared, while markets with structural large vacancy rates – Paris’s outer ring, Manhattan, San Francisco and LA – are likely to suffer more. Above and beyond WFH, which will undeniably play its part in the office cycle, we continue to think the main driver for occupational demand will remain the economic cycle and the quality of workspace.

Working from home employee surveys

A series of employee surveys have been carried out during the pandemic by the likes of Deloitte, Bain & Company, Savills, Gensler, McKinsey and the BCG. In summary these revealed:

Positive WFH findings

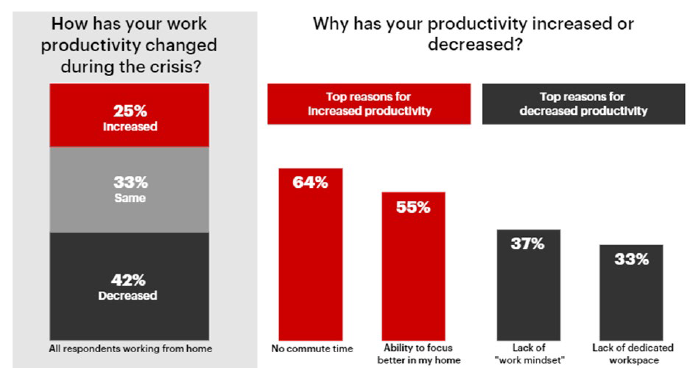

- More than half of employees generally consider they have either maintained or increased productivity while forced to WFH. This is mainly due to the absence of commute and a better ability to focus at home.

- The same proportion of workers believe their colleagues are as or more productive than before lockdown.

Negative WFH findings

- About 40% say lockdowns have had a negative impact on their wellbeing.

- More than 40% believe their productivity has declined, according to a global Bain & Company survey, with top reasons cited being motivation and workspace set-up.

- What WFH workers miss most: 45% miss social interaction, 31% miss collaboration, 25% miss networking.

The biggest reasons for increased productivity are therefore from gains made by not commuting and an ability to focus better, while the top reasons for decreased productivity relate to motivation and set-up.

Figure 1: Employee survey results – productivity

Source: Bain Global Retooling Survey (n=953). Survey conducted April-May 2020, excludes “I don’t know” answers.

Looking forward

A recent survey by Savills suggests that, post-pandemic, most UK workers would like to WFH only one or two days a week, with only 6% preferring full time. Meanwhile, a series of Gensler 2020 workplace surveys showed that more than half of US employees, over two-thirds of UK employees and over 70% of France employees would prefer a hybrid work model (employees surveyed who were already using a hybrid work model reported the most positive impact for creativity, problem-solving and team relationships). Only 5% of employees in France would like to work full time from home. A May 2020 survey by the BCG indicates that 60% of employees want flexibility on either when or where they work, going forward.

In summary, workers want a hybrid model where they would choose the office to be more productive and collaborate but would work from home for convenience and safety.

Will we still need offices?

Employers will need to give employees a good reason to wake up earlier and spend time and money commuting to work in an office. We think there are compelling reasons to do so:

Maintaining and nurturing a corporate culture: What is the value of corporate culture? How do you maintain this social capital without regular and sustained interaction between employees? How do you coach, mentor, motivate, advise or provide feedback to employees when working remotely? An office is a place of common purpose and can also be used to embody a brand for existing and future employees, clients and stakeholders.

Collaboration: There is an impact on creativity, problem-solving and innovation with WFH. Similar to the argument for open space office versus individual desk offices, which was developed by tech tenants (WeWork etc), collaboration is one of the biggest benefits of being in an office.

Being in an office: According to a Bain & Company survey, 42% of employees cited that WFH had decreased their productivity – their top reasons were lack of “work mindset” and lack of dedicated workspace.

On-boarding new employees: How does a new employee quickly embrace its new employer’s corporate culture without the social interaction and face-to-face collaboration? How easy is it to build colleague relationship without offices?

Clients: Building new or nurturing existing customer relationships, responding to clients requesting face-to-face meetings or wanting to visit a vendor’s office (due diligence reasons for example).

Employee guilt: Fear of missing out (FOMO) versus WFH. Once colleagues, executives and managers return in part or in whole to the office, some employees might fear they are missing out on social interaction, office politics, after-work gatherings, mentoring or might even suffer from a lack of visibility, etc.

Employees’ wishes: According to a Gensler survey, despite more than half of workers preferring a hybrid model, 90% of employees want an assigned desk when back in the office.

Employers’ wishes + vaccines: Employers want their employees to be back in person but won’t do it until the environment is deemed safe. How hard can they push it? If infection rates reduce, more employees get vaccinated and those employees are happy to visit other social places – restaurants for example – the stigma of going back to the office should be assumed largely removed. This would, of course, also require schools to have reopened and for people to be comfortable back in public transport. Offices could also host testing or future vaccination facilities or consider whether vaccines should be an appropriate job prerequisite, which could be politically and legally sensitive.

Long-term prospects for 100% remote work: What is the outlook for jobs which can be done remotely 100% of the time without any need for face-to-face interaction? There is an open question as to whether the role could be taken off-shore and performed in a cheaper location, as well as whether the function could in the long term be automated or better performed by AI?

Competitiveness: Employers will need to ensure an office is not just fit for purpose but also attractive enough so that it becomes a competitive advantage in the war for talent attraction and retention.

Wellness-friendly and green offices: Employers will have to offer employees the ability to work, meet and collaborate in well-located and easily accessible prime offices with strong heating, ventilation and air conditioning, as well as wellness, technology and sustainability characteristics. In large part, the advent of the modern, “wellness”-aware, carbon-minimising office was already underway before the pandemic, and this should accelerate post-Covid as both employers and landlords race to build their green credentials, dependant on financial capacity and desire to make them fit-for-purpose. This could increase transaction activity from passive or semi-passive institutional owners of offices into the hands of more proactive and asset managing owner/agents.

Regulatory reasons: Would authorities allow a 100% virtual office with a simple post-box address especially for regulated companies? Or will an accessible physical place where meetings with senior regulatory-facing staff can take place be required?

Figure 2: Employee/employer WFH pros and cons

Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

Safety from exposure to contagion risk from commuting and colleagues | Increased cost for IT equipment, cybersecurity |

Saving on office costs for employers | Harder to on-board new employees |

Saving on commuting costs, time and food purchases for employees | Structure – lack of routine, blurring private/work life |

Potential to better balance work and time with family | Lack of social and human interaction – missing non-verbal cues in video conferences, mental health and isolation |

Degree of flexibility in working hours | Morale and motivation |

Diversity in career aspiration – flexibility in work hours | Harder to coach, counsel, provide advice or feedback for existing employees |

More privacy/focus (although not if home-schooling), attending to young children or vulnerable relatives | Longer hours at home and FOMO. Feelings of guilt of not being in the office and temptation to always be logged on to compensate for lack of visibility |

Time and cost savings on client meetings/business travel | Harder to build customer & colleague relationship |

Change in measuring employee performance: presence does not equal effectiveness and productivity | Less collaboration with impacts on innovation, problem-solving and creativity – more individual output |

Differing personal logistics. WFH relies on ability to work productively – but not everyone has home office space, internet connectivity or privacy/ability to focus | |

Trust/lack of supervision – employers trust that employees generate equal output regardless of location. But to maintain that trust monitoring via “productivity” tools might be required |

Which sectors have the most potential for remote work?

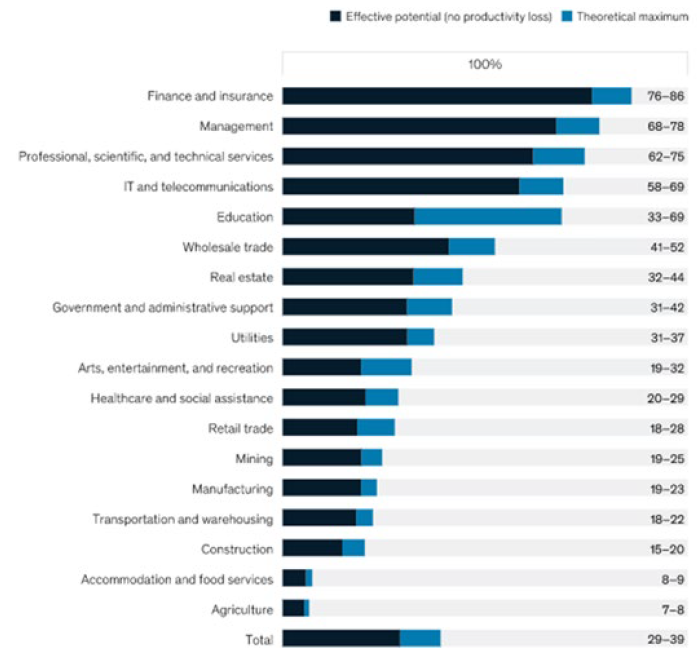

According to a McKinsey study, the top three sectors with the most time spent on activities that can be done remotely without a loss of productivity are: finance and insurance; management; and professional, scientific and technical services (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Potential share of time spent working remotely by sector in the US (%)

Note: the theoretical maximum includes all activities not requiring physical presence on-site; the effective potential includes only those activities that can be done remotely without losing effectiveness. Model based on more than 2,000 activities across more than 800 occupations. Source: McKinsey Global Institute analysis.

Although these three sectors top the potential for remote working, in London, for example, according to Savills Research, the professional services sector was the main driver of demand across the City with 33% of 2020 take-up, followed by Tech & Media with 19% and Insurance & Finance with 16%. All three sectors therefore accounted for close to 60% of 2020 City office space take-up despite being identified as the most ripe for WFH – one explanation for this is that those sectors traditionally dominate the City tenant mix.

What are senior executives in these sectors saying?

Some high-profile firms have promised their workforce a permanent and open-ended WFH structure for employees wishing to do so. Facebook’s CEO, for example, said that as much as 50% of its workforce could be working remotely in the next five to 10 years and the company has recently appointed a “Director of remote work”. Although this has made headlines, we consider the messaging is mostly directed at reassuring its workforce so as to minimise the risk of talent loss and retain talent attractivity for future hires. We mainly note that these public statements directly contrast with other statements made by senior executives of high-profile tech and financial firms which arguably should have been the most prominent advocates of WFH.

For example, John Waldron, Goldman Sachs Co-head of Investment Banking, said: “There is concern that Goldman’s vaunted culture, which leans on in-person collaboration and mentorship of junior personnel, will weaken over months of remote interaction.” Similarly, James Gorman, CEO of Morgan Stanley said: “The vast majority of our employees, [and] the vast majority of their time [will] continue to work in offices.”

How to combine workforce aspirations with business needs? The hybrid model

Most employee surveys conducted so far show that office employees want the option to WFH between one and two days a week.

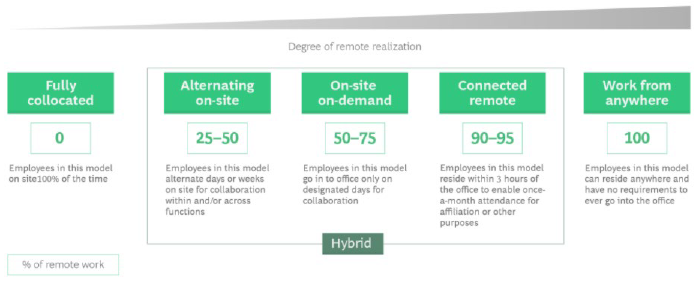

Figure 4: Remote working

Source: BCG Analysis, 30 June 2020

Offices have rarely been 100% utilised. Office REITs report that, pre-pandemic, offices were on average 80% physically utilised (ie for any office tenant, its hired workspace utilisation was never 100% but mostly around 80%), while the 20% vacancy could be explained by staff either on holiday, on sickness absence, in outside meetings or on the road. There are a number of factors to consider going forward:

Agility: Remote working need not equate with all or most employees WFH. For example, BCG suggest remote work could be structured with employees splitting their time between home and the workplace, on alternate weeks or a rotating schedule (Figure 4). Entire teams could share their office space with other teams. However, conversely, all employees could be asked to be present at designated times.

100% office presence: Every staff member present a few days a week could translate into unchanged demand for office space if this results in one or more overlapping days where most people are present. Some forecasters are predicting that WFH for one or two days a week should equate to 15%-20% less demand for space, when that appears as a little simplistic to us.

Customisation: Office space could become increasingly tailor-made to tenants’ requirements. Secondary and older unfit-for-purpose offices will suffer in leasing attractivity, rent levels and valuations, and eventually could be repurposed. Flexible space could make a comeback as tenants allow some contingency in their office strategy to account for possible employee and business growth, but also possible short and sharp declines. In addition, one size won’t fit all: different companies, business units and teams will have different requirements for WFH. Because jobs differ, the need for collocation differs too. Jobs with the most need for close supervision, innovation and on-site client interaction are likely to require more on-site presence.

Desk sharing: This is already prevalent in a number of sectors and companies with well-known benefits (mainly costs savings), but also disadvantages (uncertainty on desk location, possibility of being sat far from own team which nullifies the teamwork and cultural benefits of being in the office, need for stringent cleaning protocols when employees change desks, etc).

Are there differences between countries and why?

Recent reporting of use of office buildings seems to show wide difference between countries. For example, offices in German or French cities were between 50%-80% full when national restrictions were partly lifted between lockdowns; only 15% of office employees in France were WFH at the end of summer. In Berlin, while large companies still had a majority of their workforce WFH, small and medium-sized enterprises and public sector employees had mainly returned to their offices. Conversely, offices in US cities, London or Australia reported very low usage, generally below 20%.

Landlords have been cautious at offering firm explanations for this gap in employee behaviour between countries. Some have pointed at more hierarchical cultures explaining why employees felt compelled to go back in Germany or France. Other reasons cited were layouts of modern cities in Anglo-Saxon countries where central business districts/downtowns are more distant and distinct from out-of-town residential areas, which differ from older continental European cities where the distinction between residential and business district areas is more blurred.

We remain cautious at drawing any conclusions or early lessons on these differences in terms of the WFH impact for these national markets, and still expect that WFH hybrid solutions will impact all office markets globally regardless.

Politicians are starting to get involved

Politicians have also jumped on the WFH bandwagon and are considering how to approach it. For example, trade unions in Spain have recently been tasked by the government with ensuring that employees WFH are adequately compensated by employers for any utilities or IT expenses. If anything, this would make the costs of WFH more explicit for employers.

Politicians in Germany are debating whether employees WFH should be subject to a special tax given the cost savings they benefit from by not using transportation or not spending on food near their physical office. Others argue that the carbon impact of not driving to work or using the transport infrastructure should also be accounted for positively. Some are thinking of drafting a law to make it compulsory for employers to offer at least one day of WFH in office job contracts.

Living with Covid = social distancing = less densification = more demand for space?

After decades of tenants looking to compress workspace per employee – known as “densification” in property jargon – in order to save costs and allegedly increase productivity, the need for social distancing and the onus for employers to make offices a more attractive proposition for employees might prompt a 180-degree shift.

If offices need to be certified Covid-secure, bearing in mind future virus variants and assuming the virus becomes endemic like the flu, then could this increase the amount of required space per desk – some estimates are around 20% more space required – and de-densify the workspace? Could we go back to 15 square metres per employee from the current five square metres? Could we see the return of the enclosed individual office space combined with more and larger collaborative workspace such as meeting rooms, discussion areas, etc. This again might increase the amount of office space required.

Turning to office towers and skyscrapers, we think they will continue to be relevant in the office landscape as long as they are able to adapt to new demands in wellness, flexibility of workspace design, are easy to refurbish and most importantly are well located. On lifts, we consider that as long as these are equipped with proper ventilations and well managed to deal with traffic flow, then spending up to a few minutes in a lift should be no more of a barrier from a pandemic standpoint than spending a longer amount of time on public transport.

What could be lost in the transition?

Once the hybrid model becomes an established practice, would companies still require disaster recovery space when an entire workforce can function remotely in an emergency? We think that asset class might be in jeopardy. Away from that, we have already mentioned the likely polarisation between prime and fit-for-future purpose offices and a second or even third tier office market which could disproportionately see values and rents racing for the bottom as their space becomes unlettable.

Impact on leasing market

In our direct conversations with large office landlords, we have been given frequent anecdotal evidence that many existing tenants continue to roll over leases even when offered the option to break their existing leases or give back office space. This is kicking the can down the road, but is understandable. The positive catalyst offered by vaccines and the prospect of an economic recovery is mitigated by the uncertainty of WFH or future virus variants/lockdowns. This means a number of firms simply have no firm visibility on how much space they will require – hence rather that commit to long-term decisions on workspace they prefer to wait for the fog to lift.

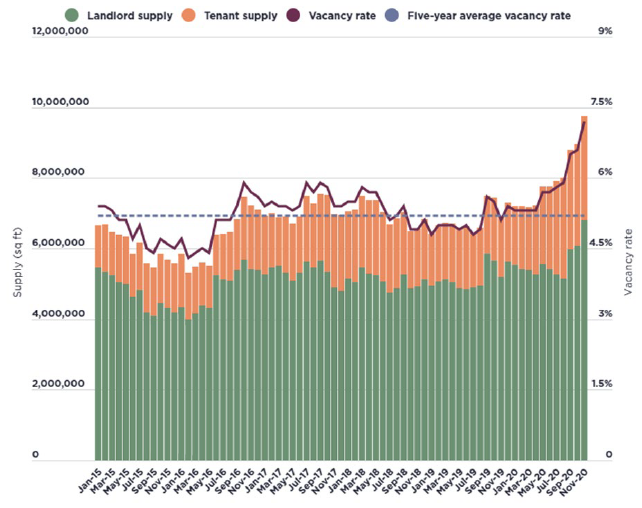

However, there is mounting evidence that as a whole office space supply is increasing while demand is reducing, which is pushing vacancy rates up. In London, according to Savills Research, from January 2020 to November 2020 space take-up is down 59% year-on-year while most of the demand is focused on grade A space. A large part of this is due to the market stalling and potential tenants generally unsure about post-pandemic space requirements, a potential economic recession or previous uncertainty on a post-Brexit trade deal. There remains 10 million square feet of City office space requirements, which is up 6% year-on-year (Figure 5). About a third of the development pipeline is pre-let for 2021 which partly de-risks leasing uncertainty for landlords, but obviously leaves a substantial portion of speculative space to be leased. This could put pressure on rent levels, concessions granted etc. However we consider the brunt of the adjustment should be felt by non-grade A office stock.

Figure 5: City supply and vacancy rate

Source: Savills Research.

According to Savills Research, lease incentives should increase in every large city in the next six months, except perhaps Shanghai. The proportion of landlords willing to offer more flexible lease terms should increase especially in London, Dubai and San Francisco, and to a lower extent in Paris. In Europe, Berlin looks like the most stable capital.

From a vacancy rate and rental declines perspective we expect the most impacted markets will be Manhattan and San Francisco in the US; non-prime, second-hand office stock in London; and the area of La Defense in Paris.

Sub-leasing: Another issue is the amount of office space which could remarketed as tenants try and sublet their unused space. Estimates in major US markets or London vary. In the City, about 30% of space supply is tenant-controlled, according to Savills, which is broadly the same as in the San Francisco Bay Area or Manhattan, according to Cushman & Wakefield. Although this would increase pressure on vacancy and rent levels, many office landlords allow subletting in their leases and usually facilitate these conversations in order to maintain some control on the process, be that which sub-lessees are contracted with, or rents levels. We think it is mostly non-prime offices which might primarily suffer from increased space take-back and subleasing. We could see increased polarisation between prime and non-prime office space.

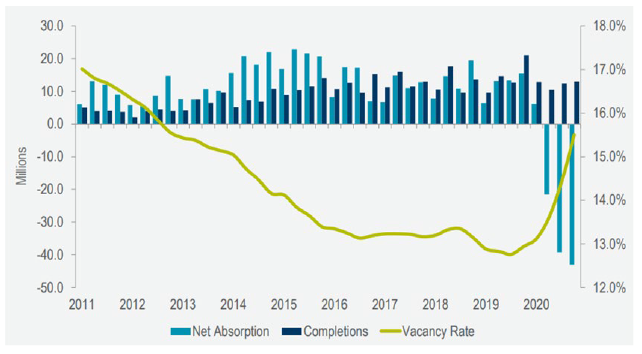

We are seeing the same dynamic in US cities with net absorption (demand less supply) turning sharply negative, which is pushing vacancy rates to 16%, which is back to 2012 levels, from around 12% earlier this year, according to Cushman & Wakefield (Figure 6).

Figure 6: US total net absorption, construction deliveries (MSF) & vacancy rate

Source: Cushman & Wakefield Research.

Summary

At Columbia Threadneedle Investments we remain comfortable with offices as an asset class and continue to think fundamental considerations will prevail when investing in bonds from office landlords in the REIT investment grade space.

Although we expect WFH to disrupt demand for space in the various local office markets, we remain confident that prime modern offices products in well sought after city centre locations with strong transportation links will continue to show occupational resilience and remain attractive in the investment market. We also expect office landlords to focus their portfolios on workspace that is best-positioned in terms of wellness, technology and sustainability.

In terms of location, we are most confident in large cities in Berlin and Germany, London City and West End prime grade A, while we expect a more marked correction in London grade B or second-hand space, and in Manhattan and San Francisco and the Paris outer ring.